Breath Biopsy could diagnose IBD via VOCs produced in the gut

IBD causes bacteria in the colon to produce an altered fermentation profile that through gut permeability can be traced from VOCs on breath

| Publication information: Arasaradnam et al., Non-invasive exhaled volatile organic biomarker analysis to detect inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)., Dig. Liver Dis. 48 (2016) 148–153. DOI: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.10.013

Disease Area: Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Application: Precision Medicine Sample medium: Breath Products: Lonestar® VOC Analyzer Analysis approach: FAIMS Summary:

|

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of autoimmune diseases primarily affecting the colon and small intestine. The principal types of IBD are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). IBD is common, and affects approximately 1 – 1.3 million people in the US1.

The cause of IBD is not entirely understood, but it is widely believed to be the result of complex interactions between an individual’s genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers (e.g. diet, lifestyle, etc.) and the influence of an individual’s gastrointestinal bacterial colonies.

At present the diagnosis of IBD and the differentiation of disease types takes a multi-modal approach that includes clinical, histological, serological, radiological and endoscopic observations2.

Accurate disease stratification is vital for determining the best treatment strategy, but at present 10 – 15% of patients elude correct categorization. Accurate phenotyping often requires endoscopy of the intestine, which is high cost, uncomfortable, has high non-compliance rates and can result in complications such as perforation of the bowel3,4.

Metabolic VOC biomarkers offer a non-invasive route to the accurate stratification of IBD patients. They also offer a potential means of determining which patients will develop more severe disease phenotypes, and who will benefit most from expensive biological and/or immunomodulating agents5,6.

Breath Biopsy® for IBD diagnosis and stratification

To determine whether breath VOCs offer an effective route to diagnosis and stratification of patients with IBD, researchers have used Owlstone Medical’s Lonestar VOC Analyzer which uses FAIMS technology to see if patients’ breath VOC profile can be used to distinguish IBD patients from healthy controls, and to also distinguish those with Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)7. IBD-related alterations to the gut permeability can result in markers originating in the gastrointestinal tract appearing elsewhere in the body. This can lead to elevated levels of IBD-related VOC biomarkers in exhaled breath.

A total of 76 subjects were recruited for the study, 54 of which had histologically confirmed IBD (29 UC and 25 CD) as well as 22 healthy controls. The predictive performance of the data from FAIMS analysis of exhaled breath samples was studied using a pipeline consisting of wavelet transformation, feature selection and a sparse logistic regression classifier. This was used to classify samples and calculate sensitivities and specificities as part of a 10-fold cross-validation.

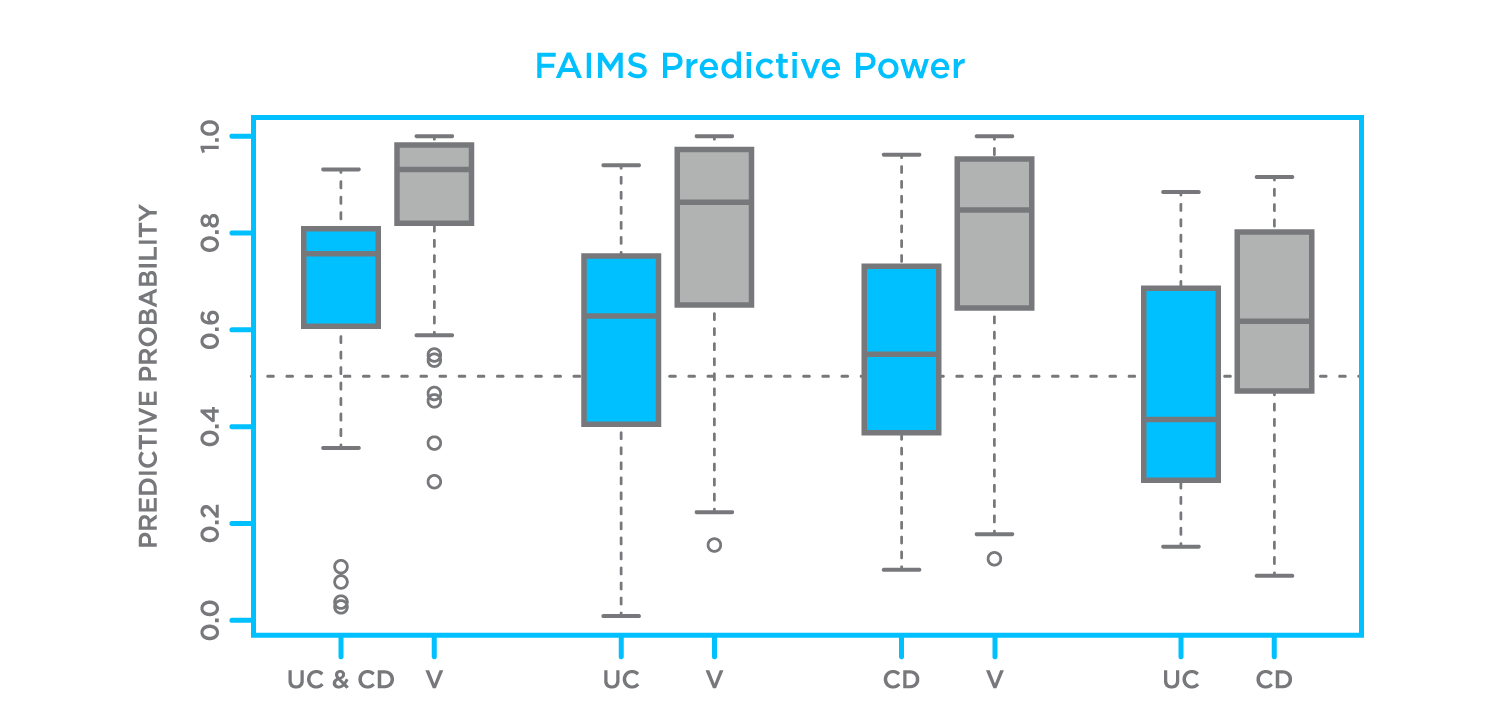

The box plot (Figure 1) shows the predictive power of IBD (UC and CD) vs. controls, UC vs. controls, CD vs. controls and finally UC vs. CD.

FAIMS predictive power

Figure 1. Predictions of classifier to different combinations of diseases and controls (UC – ulcerative colitis, CD – Crohn’s disease, V – volunteer (healthy control)). The study used the Lonestar VOC Analyzer (FAIMS) to analyze VOC biomarkers in breath7.

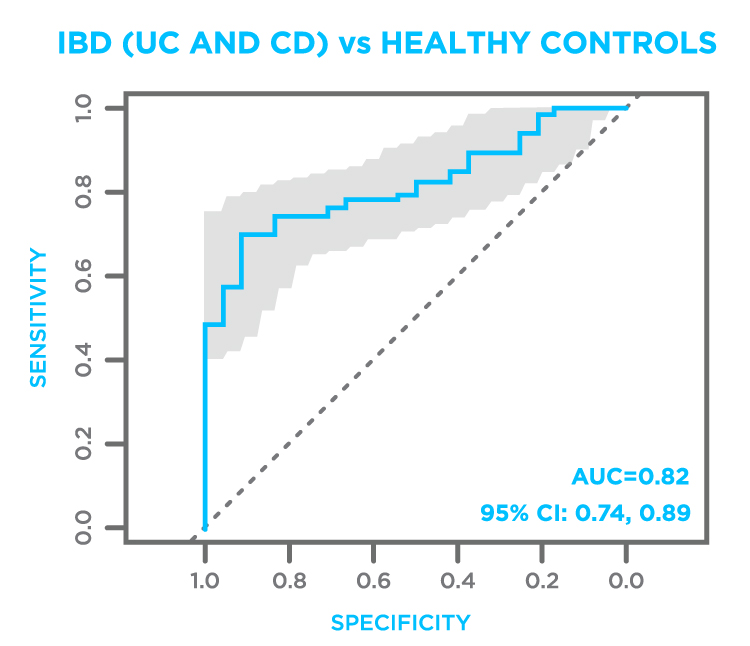

The analysis showed that patients with IBD could be distinguished from control patients using FAIMS analysis of VOCs in breath samples with a sensitivity of 74% (95% confidence intervals (CI): 0.65–0.82) and specificity of 75% (95% CI: 0.53–0.90), p-value 6.2 × 10−7. The AUC (area under curve) was 0.82 (95% CI: 0.74-0.89) (Figure 2).

FAIMS could distinguish those with UC from those with CD with a sensitivity of 67% (95% CI:0.54–0.79) and specificity of 67% (95% CI: 0.54–0.79), p-value 9.23 × 10−4. The AUC was 0.70 (95% CI: 0.60–0.80).

Figure 2. Receiver operator curve (ROC) plot of IBD (UC and CD) vs. healthy controls.The study used the Lonestar VOC Analyzer (FAIMS) to analyze VOC biomarkers in breath7.

This study demonstrates the utility of FAIMS exhaled VOC analysis to distinguish IBD from healthy controls, and UC from CD. It conforms to other studies using different technology, whilst affirming exhaled VOCs as prospective biomarkers for diagnosing IBD.

In addition to breath-based VOCs, fecal VOCs observed via a Headspace Sampler, also have the potential to serve as a complementary, non-invasive technique in the diagnosis of IBD.

Owlstone Medical are currently collaborating with Functional Gut Diagnostics and Functional Gut Clinic to discover, validate and commercialize novel tests that link VOCs detectable on breath to digestive health disorders, with a first study initiated on gut dysbiosis.

You can find out more about the history of non-invasive gastrointestinal biomarker research in our blog.

References

- CDC – Epidemiology of the IBD – Inflammatory Bowel Disease, (n.d.). https://www.cdc.gov/ibd/ibd-epidemiology.htm.

- Kurada et al., Review article: breath analysis in inflammatory bowel diseases, Aliment. Pharmacol. & Ther. 41 (2015) 329–341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apt.13050.

- Blotière et al., Perforations and haemorrhages after colonoscopy in 2010: a study based on comprehensive French health insurance data (SNIIRAM)., Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 38 (2014) 112–117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2013.10.005.

- Friedman et al., Factors that affect adherence to surveillance colonoscopy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease., Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 19 (2013) 534–539. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182802a3c.

- Devlin et al., Evolving Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treatment Paradigms: Top-Down Versus Step-Up, Med. Clin. North Am. 94 (2010) 1–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2009.08.017.

- Yoshida et al., Diagnosis of gastroenterological diseases by metabolome analysis using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, J. Gastroenterol. 47 (2012) 9–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00535-011-0493-8.

- Arasaradnam et al., Non-invasive exhaled volatile organic biomarker analysis to detect inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)., Dig. Liver Dis. 48 (2016) 148–153. Download paper.