Engineering Multiplexed Synthetic Breath Biomarkers as Diagnostic Probes

| Publication information:

, , , , , , , , , , , , Disease Area: Lung Cancer. Sample Medium: Breath. Analysis Approach: PTR-MS. Summary:

|

Introduction

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are a promising set of molecules that are detectable in exhaled breath, can be produced in the body, and have been studied for their potential to serve as biomarkers for a variety of contexts, including infectious diseases, cancer, asthma, and more (1–5). The VOCs that originate from internal processes are mostly present at very small concentrations in the breath, so picking up meaningful signatures that arise from key metabolic processes from those that have come from the background air is a key challenge of breath research. A way to circumvent this and take advantage of the non-invasive nature of breath sampling is by introducing probes into the body. These are designed to be specifically cleaved upon interaction with a key physiological pathway of clinical interest and release a volatile reporter molecule measurable in the breath. We are developing exogenous volatile organic compound (EVOC®) probes in order to take advantage of this possibility, and this approach underpins our EVOLUTION trials, whereby we are testing the introduction of an inhaled probe D5-ethyl-βD-glucuronide, that upon contact with lung cancer, is hypothesized to release the volatile reporter D5-ethanol.

Recent work has been undertaken by Wang et al., to further develop synthetic probes that upon interaction with specific pathways, can be cleaved by targeted enzymes and release a volatile reporter compound into the breath, intended for the diagnosis of disease (6). In their study, a multiplexed panel of breath biomarkers was designed based on a mechanism whereby protease cleavage results in the release of an alcohol reporter. This approach was validated in mouse models of viral pneumonia, where viral-associated protease activity is well understood, and in lung cancer, where cancer-associated metabolic changes are known to result in changes in enzymatic activity.

Methods

Viral pneumonia (Influenza A) mice models were generated by dosing 7-week-old female mice with Influenza virus through intranasal instillation. Lung cancer mouse models were generated in 6-week-old female mice by intratracheal instillation of 50 μl adenovirus expressing the Ad-EA vector. Healthy control mice for comparison were age- and sex-matched and did not undergo instillation of influenza virus or adenovirus. The synthetic sensors were introduced into the mice models by first mixing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then being delivered to the lungs through intratracheal instillation. At 10 and 30 minutes post-synthetic sensor delivery, breath was collected from the mice. Mice were placed in 10 ml syringes connected to closed valves for 2 minutes. Next, 25-gauge needles were connected and inserted through the rubber septum of 12 mL evacuated Exetainers®. Approximately 1 – 12 ml of headspace air was transferred from the syringe into the Exetainer and measured by PTR-MS.

Results

Developing synthetic sensors with cleavable volatile reporters

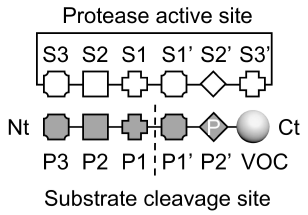

The authors first developed a system in which interaction with a specific targeted pathway would cleave a volatile reporter that can be detected in the breath. For this, they designed a probe with specific biochemical properties that when proteolytically cleaved, would release an alcohol reporter. Various in vitro tests confirmed that an aminolysis-based reaction of the probe is suitably sensitive for a diagnostic test, and crucially, did not react non-specifically to generate a reporter compound in solutions that mimic environments that would be found in the body. The resulting probe design was made from an eight-arm polyethylene glycol (PEG) nanoscaffold, attached to a substrate for the targeted protease to cleave, and the desired volatile reporter to be released. A basic schematic of the resulting probe design is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: schematic showing protease cleavage site and substrate motifs to release alcohol reporters through aminolysis. Nt: N-terminus, Ct: C-terminus, P: proline. Adapted from Figure 2 in Wang et al, 2025, ‘Mechanism of alcohol reporter generation’

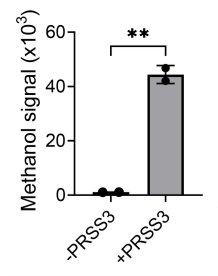

To test whether this system could reliably release an alcohol reporter and be detected, this probe design was modified to target human trypsin-3 (PRSS3). By using a trypsin-cleavable substrate as the cleavage site with methyl ester, the probe should release methanol upon aminolysis by the target PRSS3. Indeed this was found to be the case, and through in vitro experiments, including headspace analysis, methanol was able to be successfully detected.

Figure 2: The graph demonstrates the methanol signal produced by S108-Ome with PRSS3. Adapted from Figure 3 in Wang et al, 2025, ’Volatile detection mediated by protease cleavage’.

Detecting Viral pneumonia through synthetic sensors

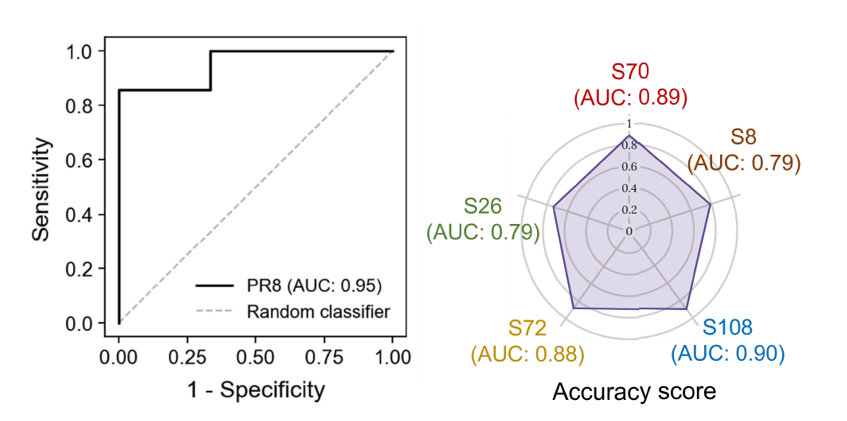

Based on the probe structure developed in previous experiments, a panel of five synthetic sensors was designed to detect influenza infection. All five contained a unique volatile reporter that could be distinguished from each other, and different substrate regions were designed to be targeted by influenza-associated proteolytic host responses, including one that had previously been shown to distinguish between bacterial or viral pneumonia. The sensors were delivered into the lungs of influenza-infected mice, and breath was collected after 10 minutes. The signals were analyzed using a machine learning tool, and diagnostic accuracy for influenza was measured by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The resulting area under the curve (AUC) was 0.95, suggesting a high accuracy for the sensors to diagnose influenza infection. The individual AUCs were also calculated for individual sensors, and a combination of the sensors was found to have the highest diagnostic accuracy for influenza infection than any one sensor alone.

Figure 3: Left: a random forest classifier was applied to independent training and testing groups of healthy and PR8 mice (n=6 or 7 mice in each group). Performance was represented with an ROC curve and estimates of out-of-bag error were used for cross-validation. Right: a radar chart showing AUC values of individual vABNs in the multiplexed panel. Significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons and two-tailed unpaired t tests; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Adapted from Figure 4 in Wang et al, 2025, ‘Development of multiplexed vABN in vivo’.

Detecting lung cancer through synthetic sensors

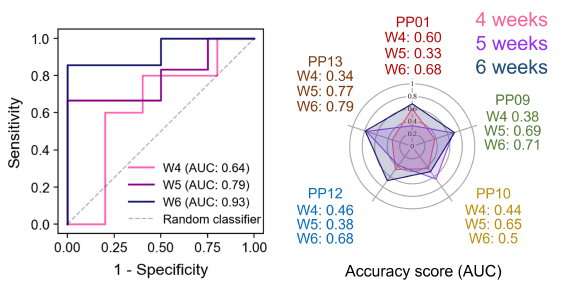

A panel of 5 synthetic sensors compatible with breath analysis based on the probe design were adapted from previous sensors used for urine analysis which targeted various proteases associated with cancer, such as serine metalloproteases. This panel of five sensors was tested using mice with lung tumors (confirmed using microCT), and delivered directly to the lungs as before 4, 5, or 6 weeks after tumor initiation. Breath from the mice was collected 10, and 30 minutes after the sensors were delivered. Diagnostic accuracies were again measured by ROC curves, of which lung cancer tumors could be distinguished from controls with an AUC of 0.64 at 4 weeks after tumor initiation, AUC of 0.79 at 5 weeks, and 0.93 at 6 weeks, showing a relationship between a larger tumor and improved accuracy. As with the infectious probes, using all five probes together improved the diagnostic accuracy of the test for cancer as opposed to any one individual probe.

Figure 4: Left: ROC curve representing the performance of a gradient boosting classifier in differentiating EA mice from healthy controls. The data was concatenated from two independent standardized cohort signals (healthy: n = 15, 16, 14 and EA: n = 25, 24, 21 for 4, 5, and 6 weeks, respectively). Right: a radar chart showing AUC values of individual vABNs in the multiplexed panel at different weeks. Adapted from Figure 4 in Wang et al, 2025, ‘Multiplexed vABNs for lung cancer detection’.

The tumors were able to be shrunk by the use of alectinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and then treatment was discontinued to mimic a relapse of cancer. The same breath-based sensors were used in these mice, and again highly accurate results were seen to detect a re-growth of tumor with an AUC of 0.88 from healthy controls.

Discussion

Historically the field of breath research has suffered from a lack of standardization in the collection, identification, and quantitation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that originate from breath. This is further complicated by the fact that there are hundreds, even thousands of VOCs in breath (7,8), which can dynamically change in abundance in response to diet, exercise, medication, circadian rhythms, and other normal fluctuations in physiology like the menstrual cycle (9–15). The VOCs from internal processes are mostly present at very small concentrations, and therefore picking up meaningful signatures that relate to disease amongst those that have arisen from the background air for diagnostic purposes is a bit like finding a needle in a haystack. This has significantly limited the number of breath tests that have been able to be translated into clinical practice. One way to improve the performance of breath tests is to utilize a probe-based approach, which has been shown to be promising as a breath test for cirrhosis (16).

Exogenous VOCs are introduced into the body through inhalation, diet, and medications. They are processed and excreted from the body through several potential routes, including in the breath. The processing of the exogenous compound in the body can be measured through the levels of the compound in the breath over time and utilized to investigate key pathways using breath compounds, an approach we call using EVOC probes (17). Two of the main breath tests currently in use in clinical practice today are based on this principle: the H. pylori breath test, and the hydrogen-methane breath test (HMBT) for diagnosing small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and carbohydrate malabsorption (CM). The H. pylori breath test involves ingesting a substrate solution containing 13 Carbon Urea (13C-Urea), and a sample of breath collected 30 minutes afterward. Unlike the cells in the stomach, H. pylori is capable of metabolizing urea to produce ammonia and carbon dioxide, therefore the presence of an H. pylori infection of the stomach is indicated by the levels of these compounds. The most common substrates used in breath tests for SIBO are carbohydrates such as lactulose and glucose. Lactulose is normally processed by gut bacteria in the large intestine leading to the production of hydrogen and/or methane. In individuals without SIBO, the administration of lactulose results in a hydrogen/methane peak in breath, within 2-3 hours due to their metabolism in the large intestine (18). In patients with SIBO, administration of lactulose results in an earlier peak in breath hydrogen/methane levels due to their earlier metabolism by the overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine.

The findings of this pre-print work demonstrate an effective design of synthetic probes that were successfully utilized for two different purposes: to detect viral respiratory infection (influenza), and cancer (lung). The multiplexed probes in combination with breath analysis have the potential to be more rapid than a urinary readout, which typically takes around 2 hours after introducing the probe for reporter compounds to be detectable in urine. Both viral pneumonia and lung cancer are key targets for advancing medical technology and offer significant potential to save lives, however, the underlying principle of synthetic probe technology for boosting the signal of endogenous VOC breath biomarkers can be applied to numerous other areas for clinical benefit, and so is an important avenue of research.

If you’re interested in probe-based dynamic breath tests, read more about the potential of EVOC probes, and see our Breath Biopsy tests that we are developing for gastrointestinal diseases, lung cancer, and liver disease. You can also get in touch with our team of breath experts to discuss expediting your biomarker discovery workflow.

References

- Danaher PJ, Phillips M, Schmitt P, Richard SA, Millar EV, White BK, et al. Breath Biomarkers of Influenza Infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022 Oct;9(10):ofac489. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac489

- Belizário JE, Faintuch J, Malpartida MG. Breath Biopsy and Discovery of Exclusive Volatile Organic Compounds for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology [Internet]. 2021;10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2020.564194

- Barbosa JMG, Filho NRA. The human volatilome meets cancer diagnostics: past, present, and future of noninvasive applications. Metabolomics. 2024 Oct 7;20(5):113. doi: 10.1007/s11306-024-02180-5

- Azim A, Barber C, Dennison P, Riley J, Howarth P. Exhaled volatile organic compounds in adult asthma: a systematic review. European Respiratory Journal. 2019 Sep 1;54(3). doi: 10.1183/13993003.00056-2019

- Chou H, Godbeer L, Allsworth M, Boyle B, Ball ML. Progress and challenges of developing volatile metabolites from exhaled breath as a biomarker platform. Metabolomics. 2024 Jul 8;20(4):72. doi: 10.1007/s11306-024-02142-x

- Wang ST, Anahtar M, Kim DM, Samad TS, Zheng CM, Patel S, et al. Engineering Multiplexed Synthetic Breath Biomarkers as Diagnostic Probes [Internet]. bioRxiv; 2025 [cited 2025 Feb 6]. p. 2024.12.30.630769. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.30.630769

- Drabińska N, Flynn C, Ratcliffe N, Belluomo I, Myridakis A, Gould O, et al. A literature survey of all volatiles from healthy human breath and bodily fluids: the human volatilome. J Breath Res. 2021 Apr 21;15(3). doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/abf1d0

- Arulvasan W, Chou H, Greenwood J, Ball ML, Birch O, Coplowe S, et al. High-quality identification of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) originating from breath. Metabolomics. 2024 Sep 6;20(5):102. doi: 10.1007/s11306-024-02163-6

- Ajibola OA, Smith D, Španěl P, Ferns GAA. Effects of dietary nutrients on volatile breath metabolites. Journal of Nutritional Science. 2013 ed;2:e34. doi: 10.1017/jns.2013.26

- King J, Kupferthaler A, Frauscher B, Hackner H, Unterkofler K, Teschl G, et al. Measurement of endogenous acetone and isoprene in exhaled breath during sleep. Physiol Meas. 2012 Mar;33(3):413–28. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/33/3/413

- Sukul P, Richter A, Junghanss C, Schubert JK, Miekisch W. Origin of breath isoprene in humans is revealed via multi-omic investigations. Commun Biol. 2023 Sep 30;6(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-05384-y

- Wilkinson M, Maidstone R, Loudon A, Blaikley J, White IR, Singh D, et al. Circadian rhythm of exhaled biomarkers in health and asthma. Eur Respir J. 2019 Oct 17;54(4):1901068. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01068-2019

- Kagaya M, Iwata M, Toda Y, Nakae Y, Kondo T. Circadian rhythm of breath hydrogen in young women. J Gastroenterol. 1998 Aug;33(4):472–6. doi: 10.1007/s005350050117

- Sukul P, Schubert JK, Trefz P, Miekisch W. Natural menstrual rhythm and oral contraception diversely affect exhaled breath compositions. Sci Rep. 2018 Jul 18;8(1):10838. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29221-z

- Miekisch W, Sukul P, Schubert JK. Diagnostic potential of breath analysis – Focus on the dynamics of volatile organic compounds. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2024 Nov 1;180:117977. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2024.117977

- Ferrandino G, Ricciardi F, Murgia A, Banda I, Manhota M, Ahmed Y, et al. Exogenous Volatile Organic Compound (EVOC®) Breath Testing Maximizes Classification Performance for Subjects with Cirrhosis and Reveals Signs of Portal Hypertension. Biomedicines. 2023 Nov;11(11):2957. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11112957

- Gaude E, Nakhleh MK, Patassini S, Boschmans J, Allsworth M, Boyle B, et al. Targeted breath analysis: exogenous volatile organic compounds (EVOC) as metabolic pathway-specific probes. J Breath Res. 2019 May;13(3):032001. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/ab1789

- Rezaie A, Buresi M, Lembo A, Lin H, McCallum R, Rao S, et al. Hydrogen and Methane-Based Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Disorders: The North American Consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 May;112(5):775–84. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.46